Arkansans Work To Make Dreams Possible Even With Student Debt

Graduating from college, getting married, having children and buying a home are all part of the quintessential “American Dream.”

By Abbi Ross

The Razorback Reporter

When author James Truslow Adams coined the “American Dream” idea in 1931, student debt was not the $1.6 trillion weight pushing down on the shoulders of the American people.

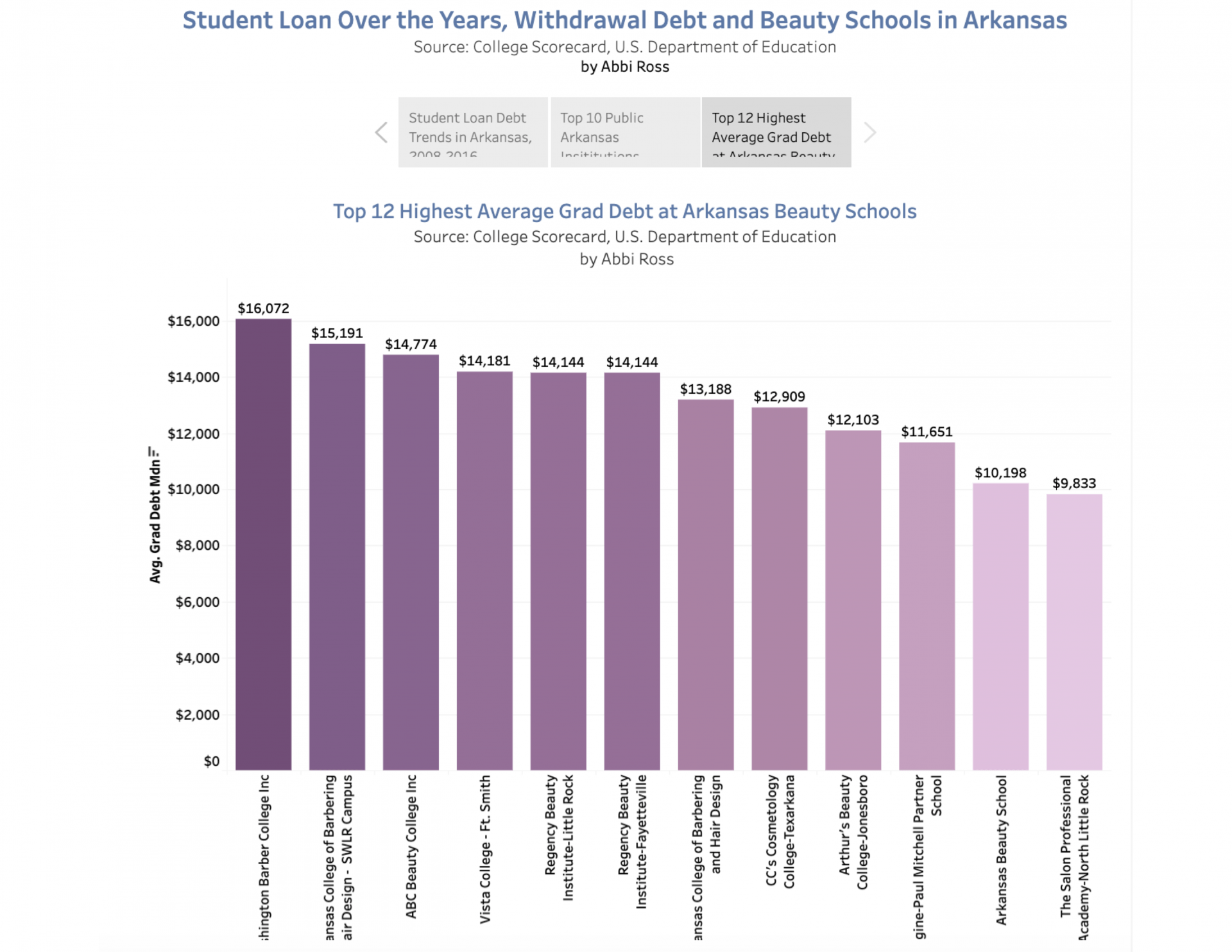

The following young Arkansans are doing what it takes to make their version of the American dream work, even with student debt. Christian Earl, a 23-year-old cosmetologist at a salon in Little Rock, has around $9,000 in student loans that he is working to pay back, he said. He works at a salon called Just Blow, A Blow Out Bar.

Earl graduated from the Salon Professional Academy in Little Rock in April of 2016, he said. Earl qualified for some grants and so he did not have to borrow as much as other classmates.

“I was not as worried because my loans are not as high as some peoples’ loans are,” Earl said.

Earl said he was able to get his current job, a month before he would have to begin repaying his loans.

Earl’s loan payment of $102 is taken from his checking account automatically each month. As a result, Earl follows a budget each month to ensure he has enough for his loan and other necessities. “You have to learn how to save,” he said.

Earl hopes to someday move to Los Angeles, yet recognizes the high cost of living on the West Coast is compounded by the difficulty of repaying the student loans.

Farther south in Dumas, Arkansas, 23-year-old Jake Lassiter is putting his degree to use at a seed and chemical store while working to pay back his student debt. Lassiter said he graduated from the University of Arkansas in Monticello in 2018 with a degree in plant soil and science.

Lassiter said he had to borrow $12,500 after he lost academic scholarships by his third semester due to flagging grades.

Lassiter, who pays around $180 a month on his loans, said that for someone with a larger amount of debt, it could be even more stressful and have a definite impact on future decisions. In his case, Lassiter said the $180 a month student loan payment is not enough to dictate any of his major decisions. “It’s an incentive to stay employed,” Lassiter said.

For others, loan payments come at a different price: it could be the difference between having the lights on at home or not. Many borrowers say providing for their families comes first.

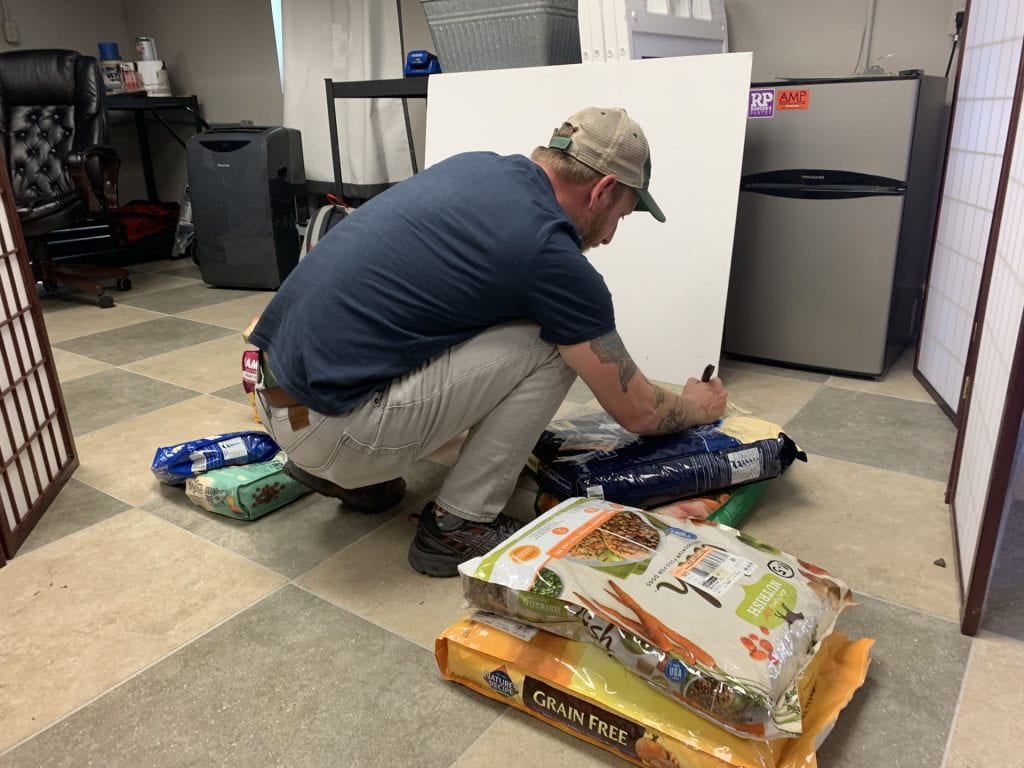

Parker Kerr, a 22-year-old from Hazen, Arkansas is a husband and father of two working to support his family.

Kerr attended Arkansas Tech University for one semester and the University of Central Arkansas for one semester before withdrawing in the fall of 2018. The reason? His partner was expecting their first child, “I had to get to work and find a house,” he said. Kerr, currently working as a security guard at St. Vincent’s Infirmary in Little Rock, said he is currently in default on his loans.

Kerr was studying nursing at UCA and said he would like to go back someday to become certified as a paramedic, but the outstanding debt is an obstacle. “It’s kind of keeping me from furthering myself in that area,” he said. “It’s almost impossible at the moment.”

One former Arkansan is going back to school on her own terms, even as she travels across the U.S. in a tractor-trailer.

Anna Ramirez, 35 and originally from Mountain Home, Arkansas, packed up her belongings in the fall of 2019 and made the decision to live with her boyfriend and travel across the U.S. with him as he works. They drive is big rig and deliver products throughout the country.

Ramirez’s academic journey started in 2004 at Arkansas State University-Mountain Home and then she transferred to ASU’s main campus to pursue a degree in photojournalism.

She withdrew in the spring of 2011 with about $40,000 in student debt and didn’t continue because she did not have financial aid for another semester, Ramirez said.

“If I had known then what I know now, I would have not gone into debt for the education I got,” Ramirez said. “Even if I had graduated that semester, the amount of debt I am in, I cannot make enough money in Arkansas to pay that debt.”

Making monthly loan payments while working full time, going to school and balancing necessities is nearly impossible sometimes, Ramirez said.

“I have struggled with it and I am very open about it,” Ramirez said. “I don’t feel like it is talked about enough, even for those who do graduate, but especially for those who don’t.”

The decision to leave Arkansas has allowed Ramirez to afford to go back to school, she said.

Ramirez is currently enrolled in an online program for education with Western Governors University, she said.

“If the only thing I can do is something drastic, I’m going to do it,” Ramirez said.