Setting the Example: How First-Gen Students

Raise the Bar, and their Debt, to Better Themselves

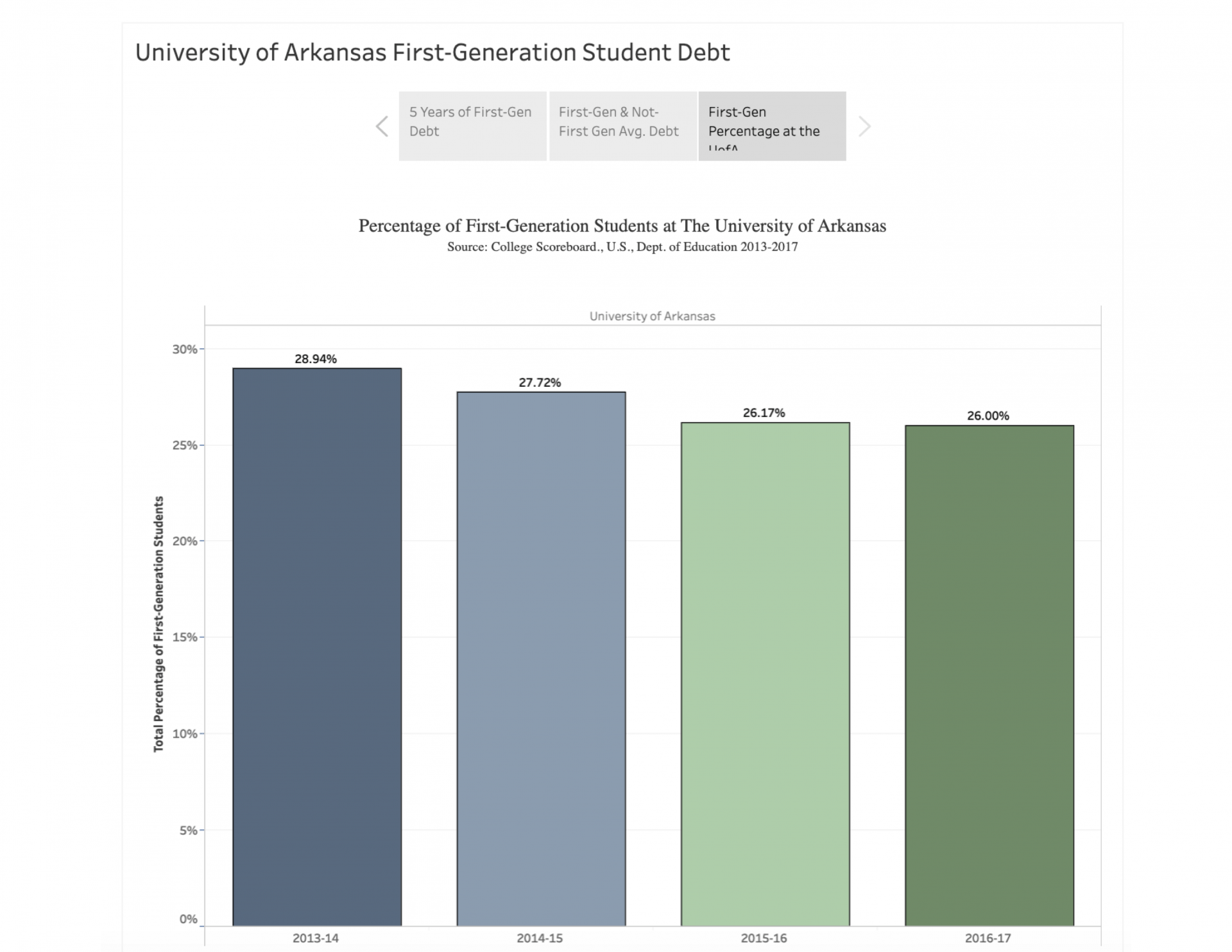

University of Arkansas first-generation students have decreased over the years, but the student loan debt has steadily increased and exceeded Arkansas’ average over the past 5 years, according to the College Scoreboard, a Department of Education database.

By Elena Ramirez

The Razorback Reporter

When individuals gain higher education, they accomplish the most effective way to raise their families’ income, according to research from the National Center for Children in Poverty. Yet higher education is expensive and intimidating, especially for first-generation students, who often have little background in navigating through the unknown world of federal loans, private loans and applications.

“It’s harder because in a way, you’re guiding yourself,” said Emily Beltran, a Rogers New Technology senior and a first-generation student who has been accepted to the University of Arkansas. “Your parents can’t give you much advice … it’s definitely hard not being mentored by your parents.”

The complexity of paying for college is just one of the many issues first-generation students need to resolve on their own. The average debt for first-generation students at the University of Arkansas has increased by 12.3% to $14,423 in 2018, over the past five years, according to College Scorecard, a Department of Education database. Dekarius Dawson, first-generation senior music major studying voice, said he has struggled with his out-of-state tuition rate. The native of Memphis, Tennessee has attended the UofA for three years and will be graduating in December with more than $29,000 of federal student loan debt, double the amount for first generation students at the U of A.

Despite that amount of debt, Dawson notices the important precedent of his work.

“To me and my family, this is a huge accomplishment, because I’m setting an example for my brothers and others in Memphis,” he said. “Receiving a degree is the new standard I’m trying to start.”

Dawson became a part of the UofA’s First-Generation Mentoring Program. He was paired with professor Timothy Thompson, who was also a first-generation college student in 1971.

Thompson recalled he was able to receive his undergraduate degree without acquiring student loans. “I can’t imagine being an undergraduate student these days and coming into these five sometimes six-figure loans and not having any idea if you will have a job when you get out of school,” Thompson said.

The three-year-old program, funded by the Honors College, provides students a mentor on campus. Students have to be the first in their family to attend a four-year college.

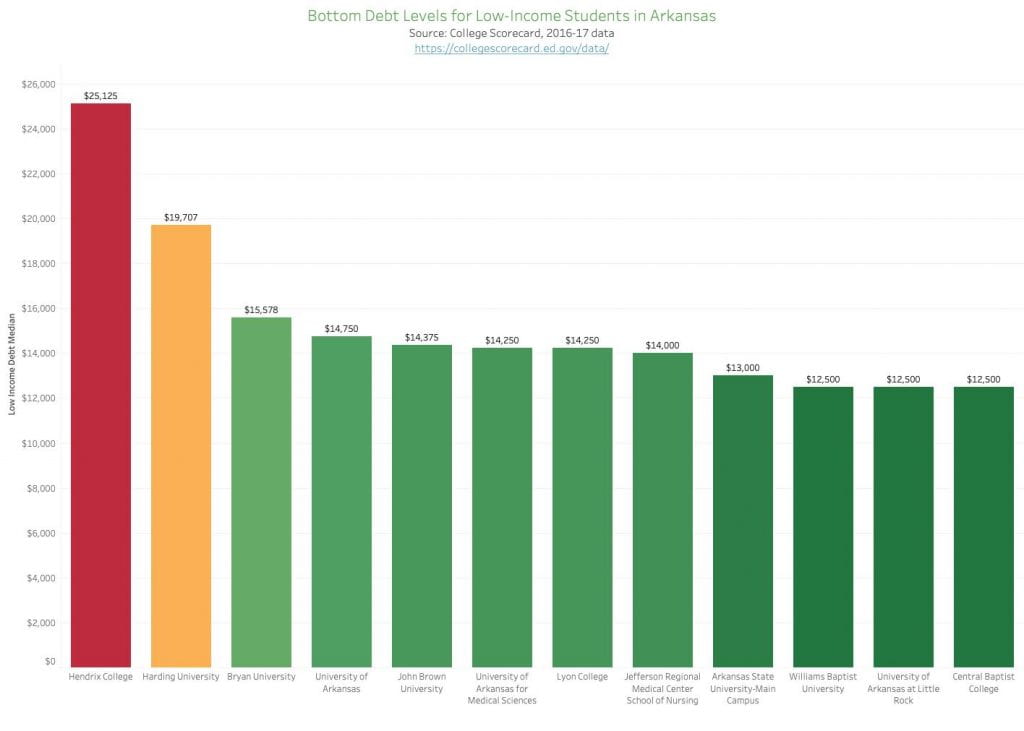

Despite the 12.3% increase in debt for first-generation students, enrollment for trends are heading in the other direction: first-generation enrollment has declined 3% over the past four years. The decrease of first-generation students is something that Chancellor Steinmetz is focused on with the new student success center that will open in the Spring 2021, said Ramon Balderas, student development specialist. “We grew very fast over the past 10 years. We are still trying to adjust to the changes,” said Balderas. “Our resources are very spread out and the new student center will help students.” About 26% of the UofA’s student population is first-generation.

The UA Student Support Services is a federally funded program that helps first-generation and low-income students. The program serves 325 students a year.

One local high school is working to support first generation students for life after campus. Two counselors at Rogers New Technology High School are pursuing initiatives on their campus to ensure students have a plan for after high school. Counselor Cindy Caudle said the Rogers New Technology High School principal wants “no graduate to be left on their parents couch in June.” Brenda Walkenbach, who has had 25 years of experience in high school counseling, wants to present high school students with multiple options. “It may not include college, it may be the workforce or the military,” she said. Caudle added that a number of students enlisted in the National Guard or fully enlisted in a branch of the military as a means to pay for college.

Every second Tuesday of the month, students and their parents meet at Rogers New Technology High School for a “Senior Wrap Session” where they are provided with guidance about post-secondary school options and resources.

Beltran, a Rogers New Technology student recently accepted into the UofA’s Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design, said she will be the first in her family to attend a four-year college. She is a part of the Early College Experience program, where she attends Northwest Arkansas Community College while enrolled in high school. She will graduate from community college with an associate’s degree.

Beltran has applied to approximately three scholarships so far and is relying on family support for the amount that cannot be covered, she said. She isn’t familiar with the loan process and has been intimidated by the essay portion of scholarships.

“Writing has always been my weakest subject, but I can go to NWACC’s (Northwest Arkansas Community College) writing center and I know they can help me there,” Beltran said.

Being first-generation motivates her to accomplish school and to better herself, she said. It will bring a change for her family.

She knows that school comes at a high expense, but said getting her prerequisites out of the way “is like a stress taken off of [her] shoulders.”

The cost of school, she said, will not hold her back.