YouTube, Instagram Offer Students a Different Kind of Job

College creators turn social media usage into revenue streams

By Hanna Ellington

The Razorback Reporter

With 90% of 18-29 year olds using at least one social media platform, according to the Pew Research Center, some UA students are taking advantage of that usage to make money.

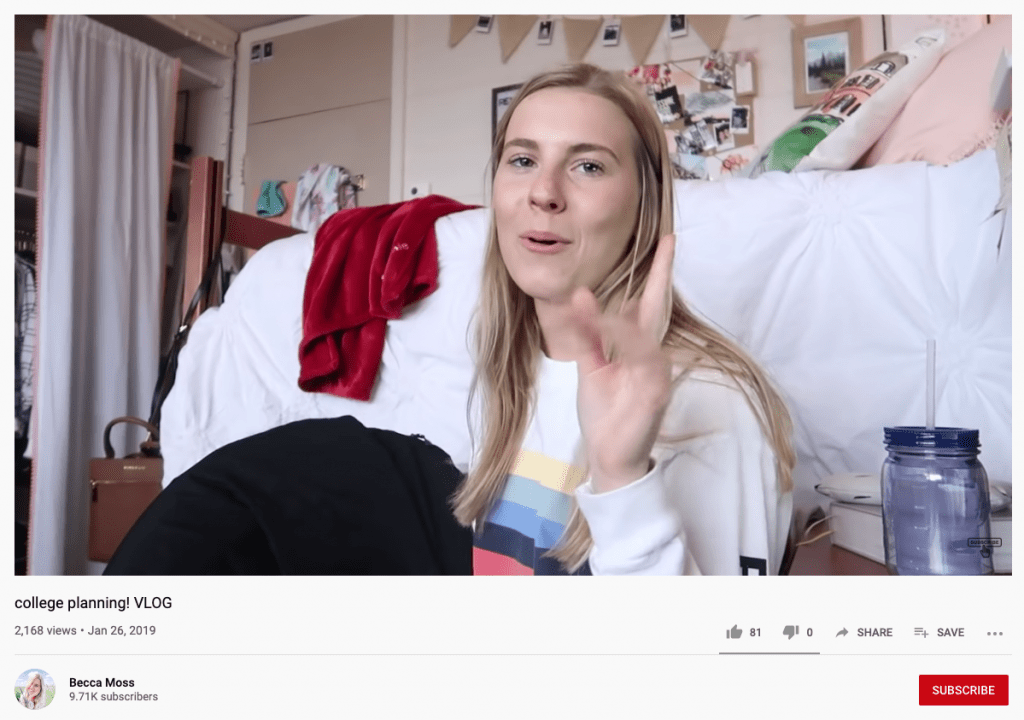

Sophomore Becca Moss began creating videos in high school. In the summer before coming to the UofA, Moss began uploading her videos displaying on YouTube her life at the UofA, she said.

“I really love watching YouTube and I really love making videos, so why don’t I just upload them there,” Moss said. “I started making vlogs because I thought it would be fun to document my life and look back on it.”

Moss has nearly 10,000 subscribers for whom she creates lifestyle, vlogs and college advice videos. That helps her connect with her audience of college-aged women. Quality videos require time and effort, which has resulted in a paycheck of up to $1,000 a month, depending on the number of views, Moss said.

Similar YouTubers include UGA student Danielle Carolan and Elon graduate Katy Bellotte, who together have over a million subscribers. Estimated paychecks for Carolan range up to nearly $50,000 a year, according to SocialBlade, a website that tracks YouTube statistics.

“[YouTube] makes it easy to be monetized and to get paid for your content, which I really appreciate, just because you do put a lot of work into it,” Moss said. “Being a college student, I pay for a lot of things myself, and I don’t have time to waste time on a hobby like that.”

Income for videos fluctuates, based on advertisements and views, Moss said. To earn money from advertisers, creators must be a part of the YouTube Partner Program, which provides creators with community resources.

Creators must have more than 1,000 subscribers and 4,000 public watch hours over the last 12 months to be eligible, according to YouTube policies, and may then make money from their videos.

Students whose profiles are raised significantly by their athletic skills have yet to be allowed to join the online payday.

That, however, could soon change. The NCAA Board of Governors announced Oct. 29 that student-athletes will be allowed to benefit from the use of their name, image and likeness.

“I think it’s a huge step in the right direction,” said Isaiah Campbell, former UA pitcher. “College athletes are putting all this work on and off the field and aren’t getting anything shown for it, like the professional athletes do by making money. I think this also should have happened many years ago, but the NCAA is trying to keep the athletes under tap as much as possible.”

That NCAA ruling could open a new way for athletes to profit off themselves, said Campbell, who recently signed with the American League Seattle Mariners.

“For other sports, like basketball and football, where jerseys are sold and video games were made off these players, it would benefit them in a huge way for paying them for people buying stuff that is theirs,” Campbell said.

Current student-athletes were instructed not to comment on any matter relating to the recent NCAA ruling.

Another platform to potentially profit from is Instagram, where users can create and post sponsored content for companies.

“On Instagram, I like to say that very pretty pictures, that’s the currency, meaning that the prettier your pictures, the further you’re going to go, the bigger impact you’re going to have, that kind of thing,” said Ramona Collins, the UA social media manager.

Visual content can be aspirational for users, Collins said, adding that people return to see more of the same content.

“With a photo, you can capture people’s imagination. They can imagine themselves being in that photo, eating the food that you share, at the concert that you’re at,” Collins said. “I think that’s what keeps people coming back; they want to see what people are doing in their images and videos.”

Engagement rate and follower count are aspects of Instagram “influencers,” who can be sponsored to post about products and brands, writer Paige Cooper said in a blog post for Hootsuite.

For some U.S. Instagram users, the “likes” feature could become private in the near future, head of Instagram Adam Mosseri announced Nov. 8.

“The likes are what we call ‘social proof.’ The more likes you have, the more probability that people are going to see the photo,” Collins said. “That number proves that people like that content.”

Removing “likes” from Instagram could have an impact on the way brands and influencers work together.

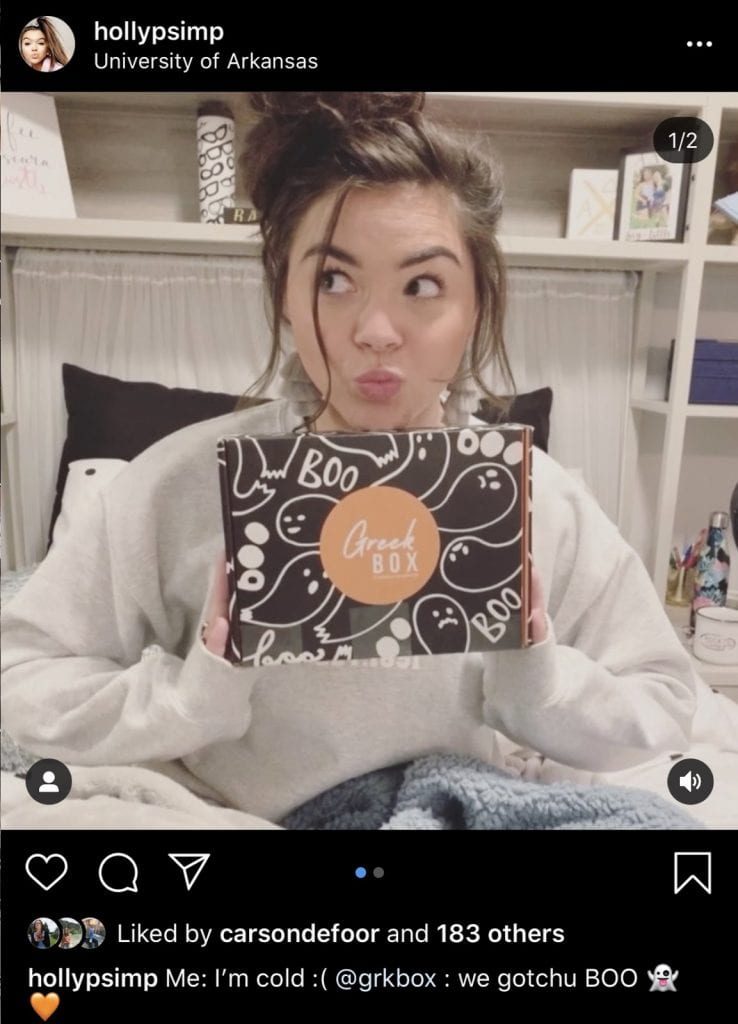

Sophomore Holly Simpson is an ambassador for GreekBox, a subscription service that includes sorority merchandise. She doesn’t make money, but she does receive a discount on her subscription and additional items, such as gifts for her birthday, she said.

She promotes the company through Instagram, where she shares her promotional code. This code provides users with a discount and allows the company to track the engagement of her followers, she said.

“When I became an ambassador, I made my Instagram public instead of private to try to reach more people,” Simpson said. “I got way more people to use my code than I thought I would.”

Some companies base their sponsorships on the number of “likes,” or engagement, but Simpson doesn’t think that should be a factor, she said.

For Simpson, being an ambassador is a stepping stone to a career that involves social media.

“It’s really cool when you’re just scrolling through Instagram and an ad pops up with your face in it,” Simpson said. “In the future, I want to be a news anchor or actress, and I think this is a cool way to get my foot in the door social media wise.”