Student Loan Defaults Have Serious Consequences

By Abbi Ross, Brooke Borgognoni and Emily Thompson

The Razorback Reporter

Whitney King had a plan. She had just graduated from Arkansas State University with her bachelors’ degree in journalism and was accepted into a masters program at the University of Arkansas.

She made the move from Jonesboro, Arkansas, to Fayetteville and thought she was set. Then she got an email on August 15 saying that a payment was overdue by 11 days — a loan she thought she would not have to start paying back until after she graduated with her masters’ degree.

King, 24, said she thinks there needs to be more information given to a borrower beforehand.

“I hadn’t taken out a loan before, so I think it would be beneficial to know the ins and outs,” King said. “It was a lot of information thrown at me on that day.

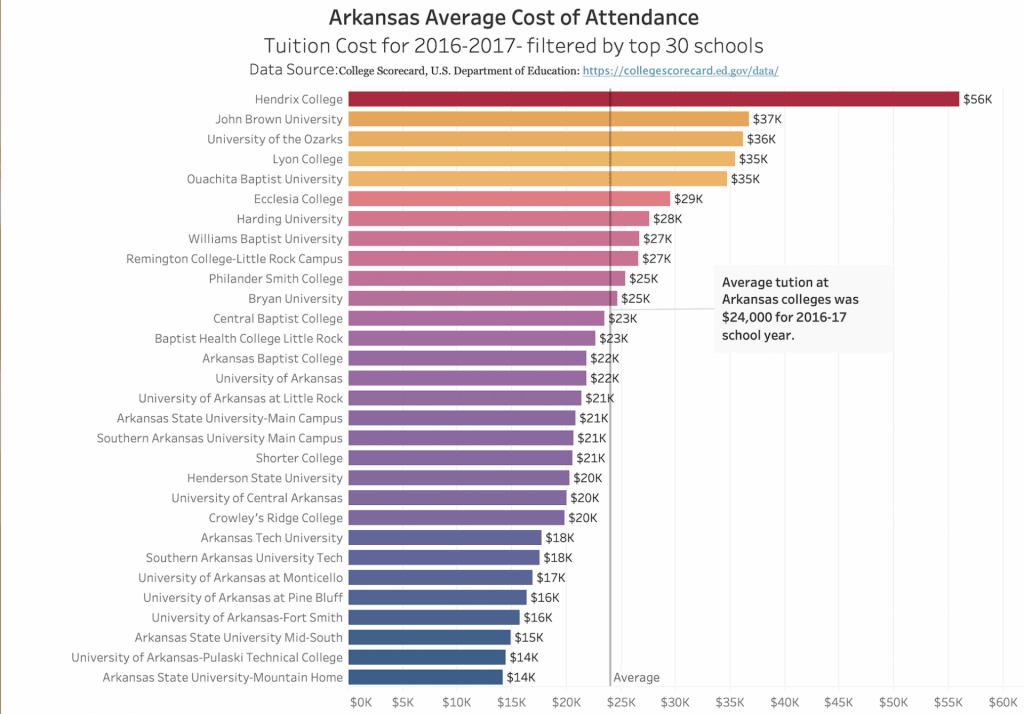

Out of all Arkansas college students that graduated between 2015 and 2017, on average, 14 percent defaulted on their student loans. The average amount of debt a student graduated school with between those two years was $14,000.

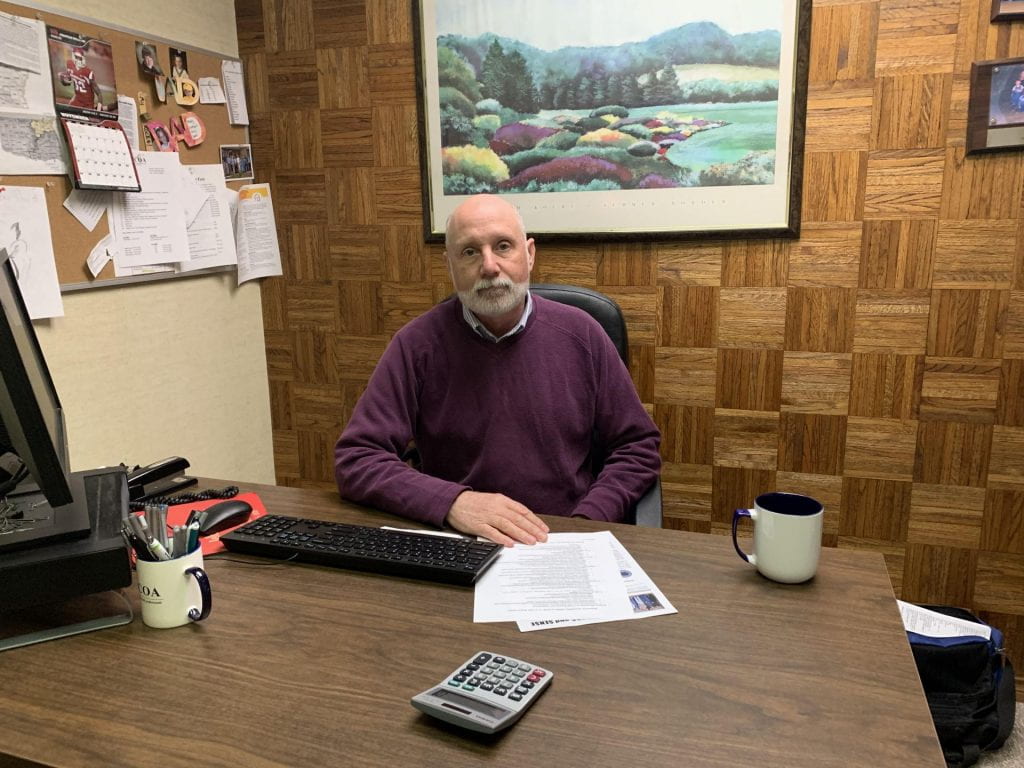

Borrowers default for various reasons, including divorce, health problems and not finishing school, Joel Doelger, Director of Community Development and Housing Counseling for the non-profit Credit Counseling of Arkansas. “There is no typical reason,” he said. A loan is considered in default after a borrower goes 270 days without making payments, Deolger said.

King said she enrolled in her graduate courses in May and thought the loan would automatically defer until after she graduated with her masters. King then got a letter informing her that loan was in default in August and quickly began the process of getting it deferred. After proving her enrollment, King is now considered to be out of default.

Todd Hertzberg, a Fayetteville-based bankruptcy attorney, said about half of his clients have student loans with some loans reaching up to $350,000.

Hertzberg urges his clients to get out of default as soon as possible, even if they plan on filing for bankruptcy. Penalties for defaulting on student loans can be severe. Unlike other creditors, student loan providers only have to send one notice before they can have employers garnish wages, meaning loan payments are forcibly taken from a paycheck. Interest rates on loans in default can spike as high as 30 percent.

There are few options for relief for those struggling to pay down student loans.

Student loans are non-dischargeable in bankruptcy, unless they pose an undue hardship. This means that even if other debt is waived through bankruptcy, student loans are not except in rare cases, Hertzberg said.

“There has been a myriad of court decisions around the country as to what constitutes undue hardship and the courts have not opened the doors very wide,” Hertzberg said. “It has been narrowed to nearly complete physical disability.”

Some undergraduates who took out loans are nervous about paying them off in the future.

Rachel Thrash, a junior advertising and public relations major at the University of Arkansas said she worries about balancing living expenses and student loan payments after graduation. She will have to begin repaying her loan six months after she graduates.

“After college, I’m going to have to start paying on an apartment and a car and all these different things and then on top of that also paying for student loans,” Thrash said.

Options for those in default are limited. A defaulted loan will be transferred from the original bank or loan servicer to a collection agency, Doelger said. Two options for borrowers after defaulting are rehabilitation and reconsolidation.

For rehabilitation, a borrower will contact the collection agency and ask for a rehabilitation plan where a payment amount is determined, The borrower will need to make nine payments in 10 months to get out of default, Doelger said.

If a borrower chooses rehabilitation they can have the default mark removed their credit report, Doelger said.

If a borrower has more than one loan, they can consolidate them, Doelger said. The consolidation process can take borrower out of default in one to two months, a quicker option that rehabilitation, Doelger said.

It also offers a wider range of payment options, but consolidation does not allow the default mark to be removed from credit scores, Doelger said. Income-driven plans are available for both options, Doelger said.

Some students do not understand the full implications of taking out student loans and the repayment process, he said.

“I think it’s human nature to be more aware of what’s going on today than what’s going to happen six years down the line when loans are going to be payable,” Doelger said.

Noel Morris, a finance professor at the Sam Walton College of Business at the UofA, said students need to approach student loans like any other loan.

“It has the same impact as if you stop paying for your car or you stop paying for your house,” said Morris. “They cannot repossess it like they would a car, but it will not go away. It will hurt your credit for about seven years.”