Black students face lower retention rates statewide

By Kate Duby

The Razorback Reporter

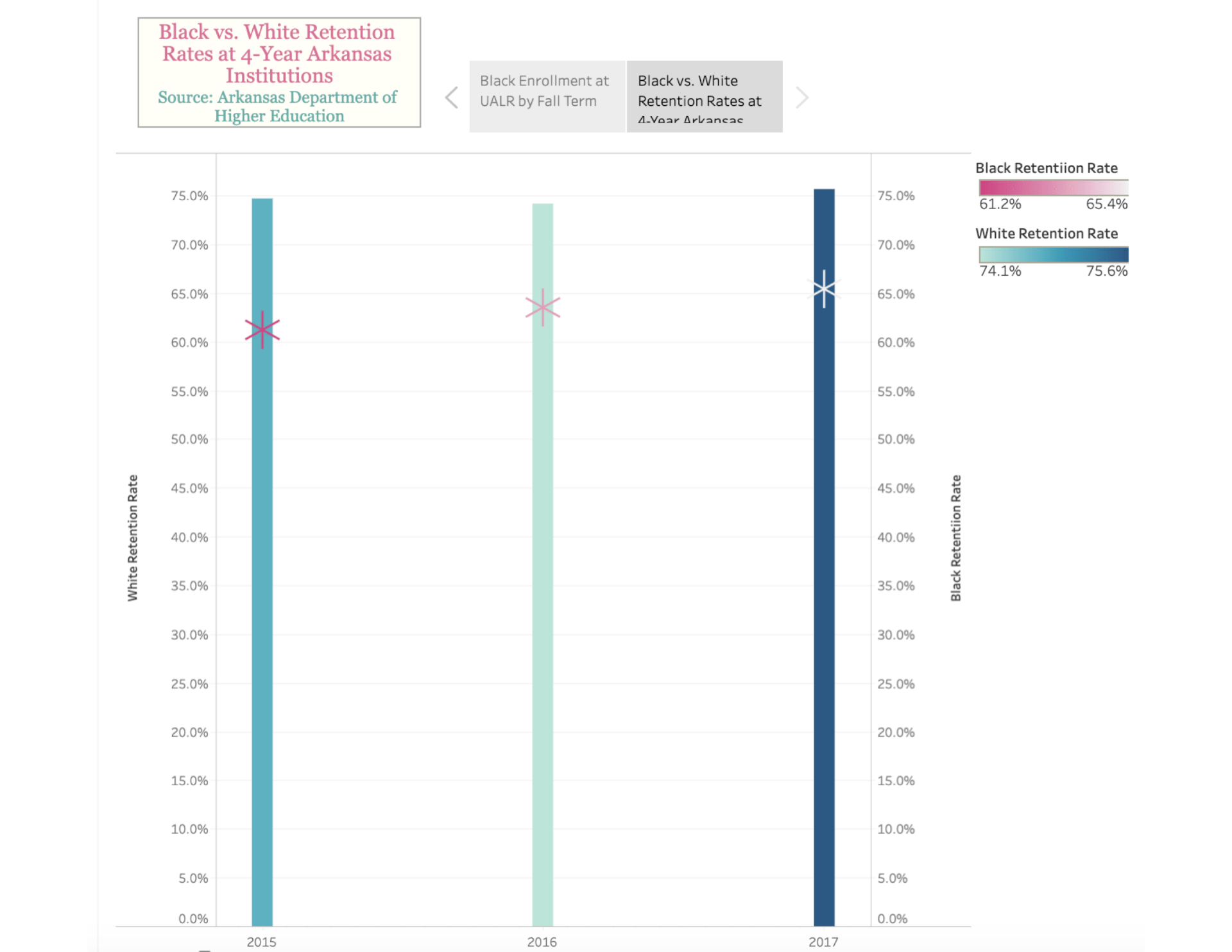

Although first-year retention rates for black students in Arkansas have increased nearly 7% since 2015, black students still face substantially lower retention rates than white students statewide, according to recent data compiled by the Arkansas Department of Higher Education.

From fall 2016 to fall 2017, black students at four-year Arkansas institutions had an average retention rate of 65.4%, compared to a white student retention rate of 75.6%, according to the 2018 Arkansas Department of Higher Education Student Retention and Graduation Report.

Retention rates generally increased for both white and black students from fall 2014 to fall 2016, but the gap remained significant, according to the report.

Kennedy Djimpe, 21, from Little Rock, withdrew from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock after his freshman year in spring 2017. After withdrawing, he spent a year out of state at vocational school completing prerequisites and certifications. He returned to UALR in fall 2018, but tuition was too high for him to re-enroll in the spring, he said.

Djimpe said he encountered personal hardships at UALR that made him not want to attend school there anymore. He also struggled to pay for college out of pocket, he said.

The average in-state tuition for the 2019-2020 academic year at UALR was around $9,530, according to the UALR bursar’s office.

During his two semesters at UALR, Djimpe accumulated between $5,500 and $6,000 in student loan debt. He is still in the process of paying off his student loans, he said.

If Djimpe could take student debt out of the equation, he “would still be in,” he said, “getting ready to finish my degree.”

Djimpe entered college as a music major but now plans to get a degree in radiography, he said.

Between fall 2011 and fall 2016, the first-year black student retention rate at UALR decreased overall from 64.9% to 60.4%, with fall 2015 having the highest rate at 68.5%, according to the 2017 ADHE Minority Recruitment and Retention Report. The report also indicates, however, that the graduation rate for black students at UALR increased by 9.7% from 2010 to 2016.

These retention patterns occur against a backdrop of declining minority enrollment at public institutions across the state.

Black students make up 25% of UALR’s undergraduate population, according to 2018 data from the National Center for Education Statistics.

This makes UALR diverse compared to the UofA, which has a black student population of 4.4%, according to the UA Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Both the Fayetteville and Little Rock campuses have seen a decline in black enrollment since 2015; UALR saw its black enrollment fall 2.7 percentage points to 27.7% in fall 2015. Between fall 2015 and fall 2016, African American enrollment at the UofA decreased 1.9%, according to the 2017 ADHE Minority Recruitment and Retention Report.

John Post, the director of academic communications for university relations at the UofA, said declining minority retention rates at the UofA are influenced by numerous factors, including financial stability, academic success, physical and emotional wellness and social engagement.