Disparity in Student Debt by Race and Gender at the UofA

By Sophia Neubaum, Emily Thompson and Brooke Borgognoni

The Razorback Reporter

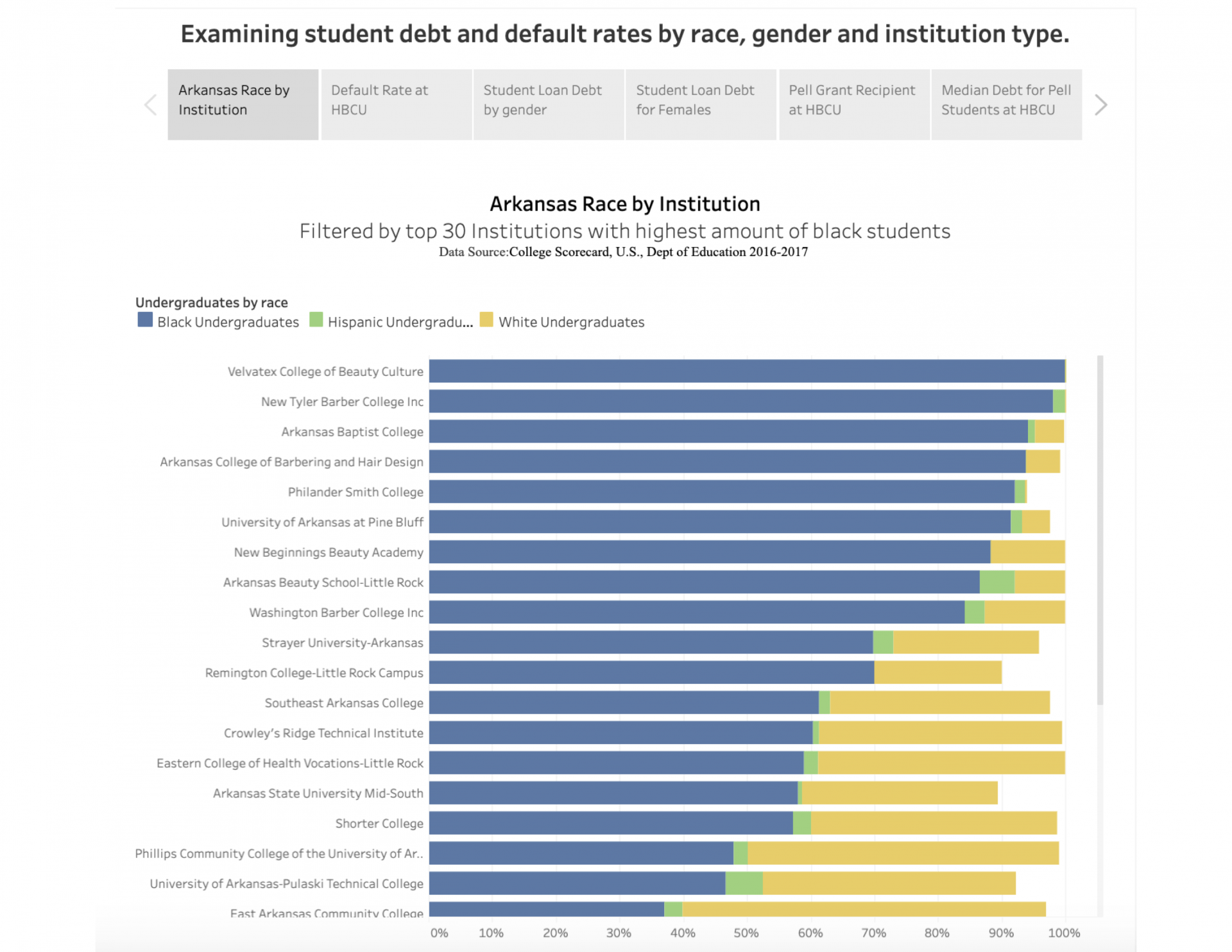

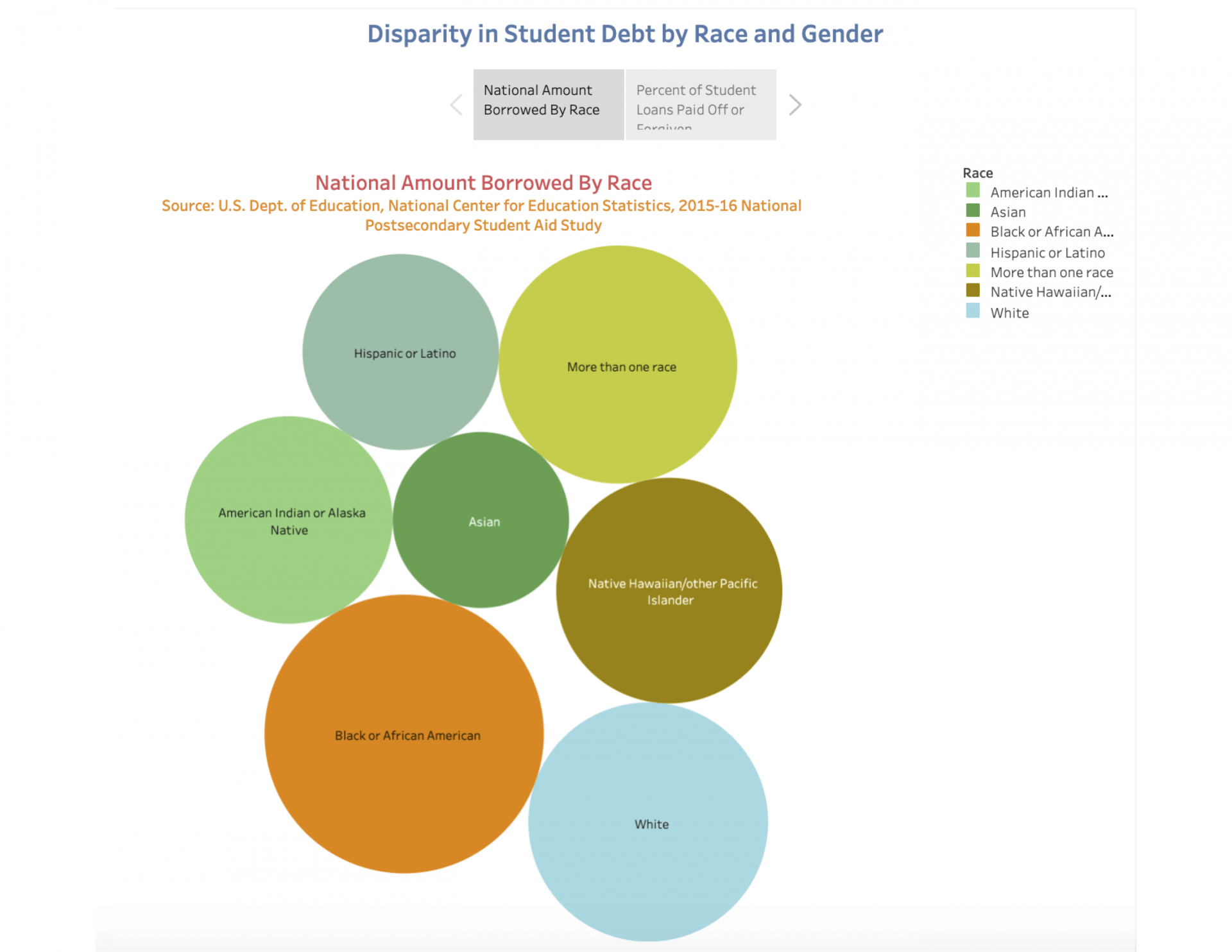

Nationally, African-American college students have almost $25,000 more in student loan debt than white students, according to the U.S. Department of Education. African-American students at the University of Arkansas cite limited financial resources, few scholarships and unequal pay as causes for the discrepancy, according to interviews.

In Arkansas, African-American undergraduate students borrowed an average of $3,000 more than white undergraduate students, with a cumulative amount of about $15,109 borrowed, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

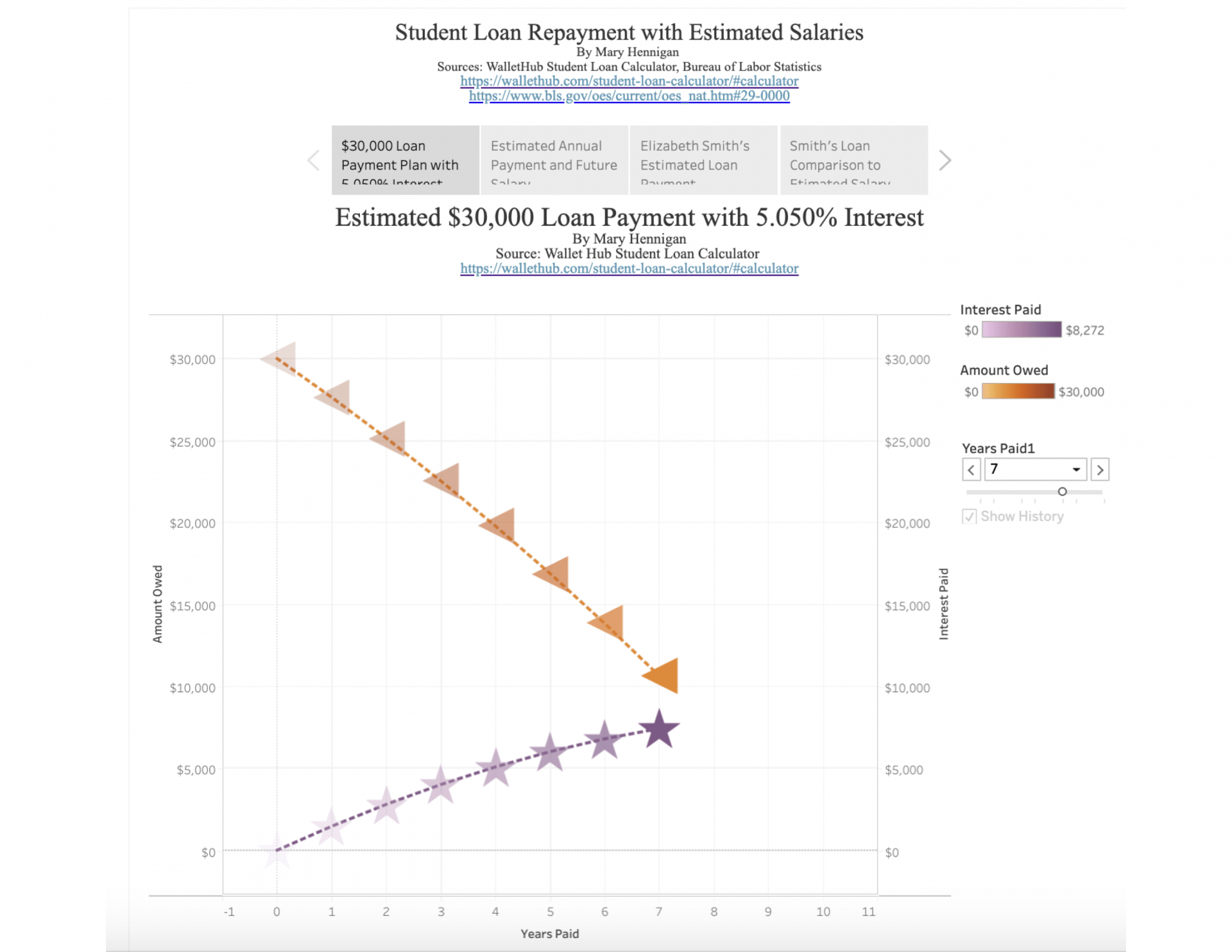

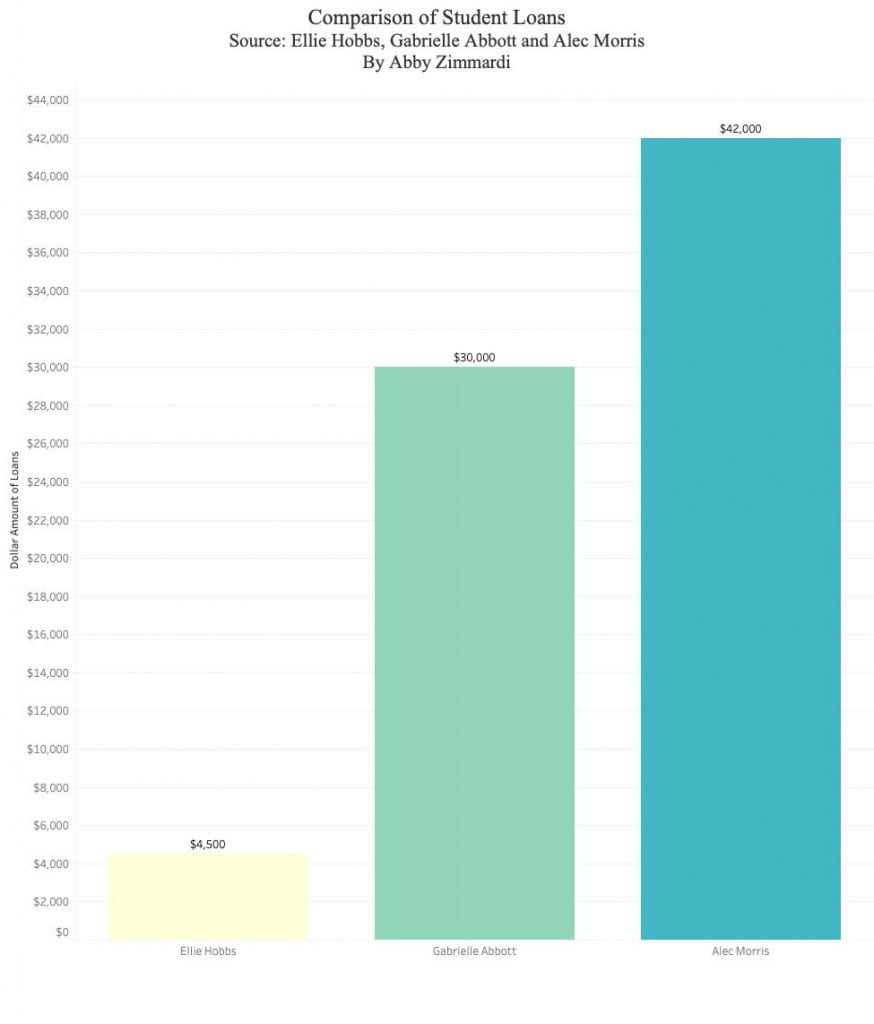

Graphics by Brooke Borgognoni and Emily Thompson

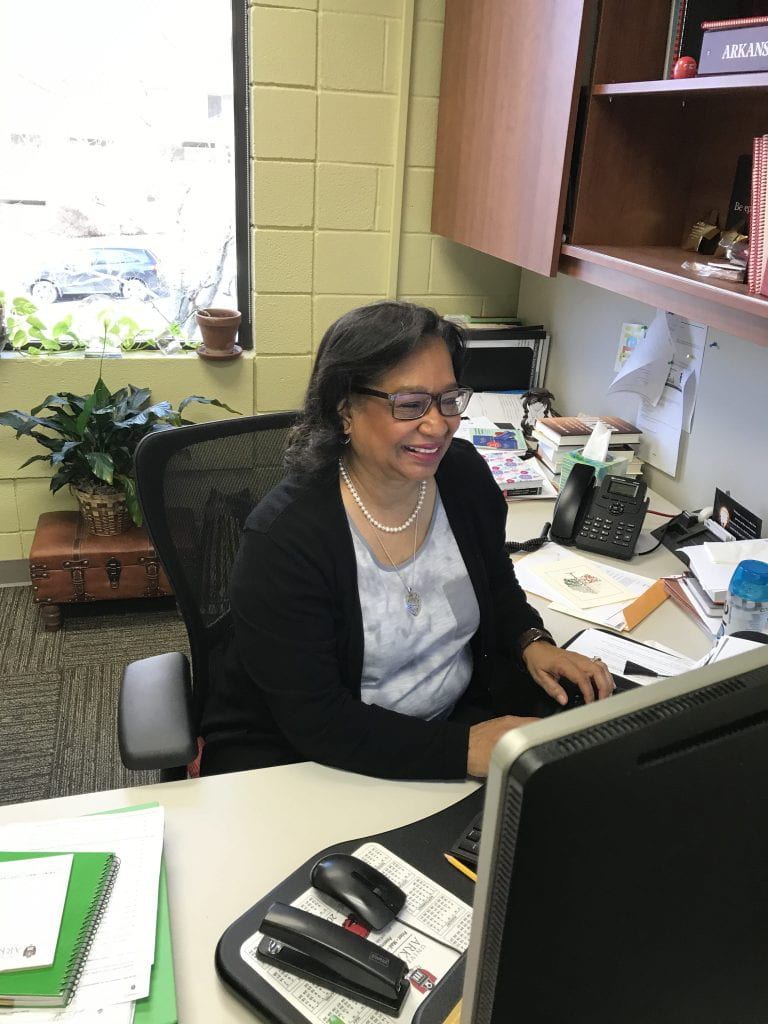

“We do know that minority students apply for loans and a greater amount of loans than any other group,” said Barbara Lofton, director of the office of diversity and inclusion in the Sam M. Walton College of Business.

This substantial difference is frequently attributed to inconsistencies in familial wealth, with white families holding nearly eight times as much wealth as African-American families, according to the Pew Research Center.

Despite this wealth disparity, some African-American students, such as UA junior Cydnee Mathis, still do not receive any scholarships or grants after she filled out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA.

“In general, for black students, they don’t have parents that are financially stable and they don’t have a choice but to use their FAFSA to pay for school, or outside loans,” Mathis said.

The only financial assistance Mathis receives is through the GI Bill for her father’s military service, she said. Although her parents do not help pay for her education, she was denied aid through FAFSA because of their income levels, Mathis said.

Mathis is one example of why student loan debt is higher for women in Arkansas, and even higher for black women.

According to a 2017 study conducted by the American Association of University Women, black women assume more debt than any other group nationally. In Arkansas, females at public schools have an average of $8,083 median debt and males have an average of $6,910. Saddled with the higher debt, black women will struggle with repayment more than others due to unequal pay in the workforce

“In general, it will take much longer for black women to pay off their student loans due to the gender wage gap,” said Felisha Perrodin, AAUW Arkansas president. Black women make 62 cents on the dollar to what white men make, Perrodin said. “This has a direct impact on their ability to reduce their debt load as well as the impact on the base salary, retirement earnings, and Social Security. The pay gap for Native and Hispanic women is even greater — 57 cents for Native women and 54 cents for Hispanic women.”

Perrodin said that eliminating the gender wage gap could help reduce the amount of student loan debt taken out by women. She cited AAUW research that shows the gender pay gap starts as early as one year out of college. “A woman with the same degree and same experience as a man can make as much as $8,000 less than a man within their first year of work,” Perrodin said.

Lofton said there are multiple reasons why debt may be higher for black women than any other race and gender. If the students do not have a job lined up after graduation, it is very difficult to pay the loan payments and may result in default. Women may also take out more loans than men because there are some women who start families early and may use their loans to help provide for the child. Lofton said said that more personal finance education could help lower student debt among women and minorities.

Overall, females at Arkansas public colleges have an average of $8,083 median debt and males have an average of $6,910 according to College Scorecard, a U.S. Department of Education database. Lofton said financial literacy education could help lessen student loan debt for women. She said Walton College is working on increasing financial literacy through their Your Money and Credit course, an introductory class about building wealth and the do’s and don’ts of credit.

There are three scholarships available for under-represented and minority students at the university, including the Silas Hunt Distinguished Scholarship, the Razorback Bridge Scholarship and the University Enrichment Scholarship, according to the university’s website. In September, UA Chancellor Joe Steinmetz announced an increase of $5 million to the general scholarship fund, according to the university website. Lofton is not confident that the budget increase will be a substantial help to African-American students, she said.

“I think some of that will trickle down, but it only goes so far. Even with that going as far as it can go, we will still need more help,” Lofton said.

Jade Easter, a U of A sophomore from Memphis, said she does not think the three scholarships for underrepresented students provide enough assistance to African-American students.

“We need more minority scholarships, but not necessarily based off of academics. It should be based off of home income, all that stuff, if you need it,” Easter said.

Megan Ramirez, a 21-year-old senior criminology and sociology major at the University of Arkansas, said she wasn’t surprised that student loan debt is higher for women.

“If you think about how women have lower incomes usually and usually don’t work as long. Some women quit working or stop working full time for kids” she said.

The uncertain job market and economic challenges for African-American families are some reasons why Arkansas Historically Black Colleges and Universities have a higher average default rate than other colleges in the state. The average default rate for HBCUs is 21 percent, compared to 15 percent for public colleges in the state, according to College Scorecard data.

There are two types of HBCUs in Arkansas — public and private. Public colleges, like University of Arkansas Pine Bluff, tend to have lower tuition. Private colleges, like Arkansas Baptist college, Philander Smith College, and Shorter college, tend to have higher tuition.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in-state tuition for the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff for the 2018-2019 academic year was $8,038. Tuition at Philander Smith College for the 2018-2019 academic year was $13,014. Tuition that same year for the University of Arkansas was $9,130.

Michael Miller, professor of higher education at the University of Arkansas, said that the environment of an HBCU might persuade a student to pay more in tuition to attend.

“They offer a different environment that’s maybe more welcoming to students of certain backgrounds,” Miller said. “And because they feel welcome and they feel encouraged to go there, they’re more likely to take out higher levels of debt.”

The United Fund study also found that HBCU students were more likely to stack private loans with higher interest rates with federal loans.

Lofton encourages students to stack private scholarships on top of other scholarships to lower the amount of money they have to borrow.

Makeda Gunter, a first-generation student in the Sam M. Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas, wished she was able to stack private scholarships but is unable to because her GPA was too low.

Gunter transferred from LaGuardia Community College in New York City to the UofA for the 2016-2017 school year. Upon being accepted to the UofA, Gunter was told she was not eligible for a transfer scholarship she has sought.

“I was really disappointed in that, so I had to take loans for actually every semester since I’ve been here,” said Gunter.

Gunter has now taken out $33,000 in loans and receives a Pell Grant, a federal grant for low income students or students with low income backgrounds.

“The Pell Grant saved my life,” said Gunter.

Gunter also credits Lofton for being helpful during the loan process and Lofton has encouraged her to search for more scholarships.

Some schools have instituted programs to help make their school more affordable.

The College of Engineering at the University of Arkansas is one example. They offer a retention program that provides financial assistance, such as scholarships, to minority students, women, first-generation students and students from underrepresented counties in Arkansas.

“Engineering has traditionally been a white, male-dominated field,” said Thomas Carter, III, an assistant dean at the College of Engineering. “The profession knows how important it is to be diversified and bring underrepresented ethnicities into the profession.”

Razorback Reporter Podcast Interview

Listen to Sophia Neubaum discuss her reporting on race and loans with Parker Tillson.