Pell Grant Covers Only Part of School Bill for Low-Income Students

With nearly 50% of all UA students needing financial aid, the UA scholarship budget is projected to increase by $5 million in the coming academic year.

By Hanna Ellington, Sophie Neubaum, and Kate Duby

Some in-state Pell Grant recipients graduate with little to no debt from the UofA, while others are not so fortunate. The average debt for UA students receiving Pell Grants is $16,000, compared to the median debt of $12,040 for students not receiving them, according to 2016-17 data from the U.S. Department of Education.

Max McKeown, a senior from Monticello majoring in horticultural science, receives the maximum Pell Grant amount of $6,195, which covers 75% of his tuition, he said. With the grant, McKeown will graduate with low to zero debt.

“The Pell Grant has helped a lot, because I get the full amount of it, so that takes away a big chunk of my tuition,” McKeown said.

Pell Grants are federal grants that students typically do not have to repay, according to the Department of Education. They are awarded to students who demonstrate great financial need. Nearly 20% of undergraduate UA students received Pell Grants in 2017-18, according to College Navigator data.

McKeown, 20, lives off campus, making tuition his only major expense under the grant, he said.

Being a Pell Grant recipient directly influenced McKeown’s decision to attend the UofA, and he thinks attending the flagship university has given him a higher quality education than he would receive at another Arkansas institution, he said.

However, the median debt for UA students receiving Pell Grants is higher than that of students not receiving them, putting into question the measurable impact of the grant.

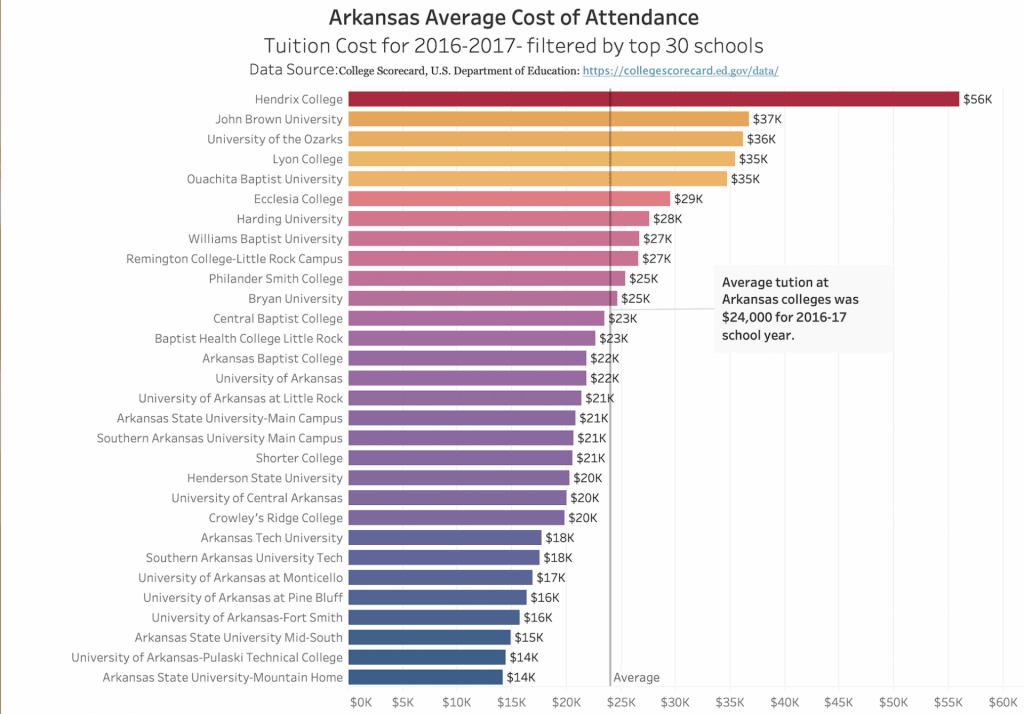

The maximum grant amount awarded is $6,195 for the 2019-2020 award year, according to the Pell Grant website. Tuition for in-state UA students for 2019-20 is $7,568, according to the UofA’s cost of attendance, with tuition, housing and other fees totaling $26,144.

“[The maximum grant] is a national number, and it’s not enough for a student to come to college,” said Phillip Blevins, director of financial aid.

In addition to Pell Grants, students can take out federal loans, participate in work-study, be awarded a Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant or be entered in the Arkansas Academic Challenge to help pay for college, Blevins said.

The nearly $4,000 discrepancy between the accumulated debts of Pell recipients and non-recipients is not surprising to Suzanne McCray, UA vice provost for enrollment. Students who have Pell Grants still can have significant personal expenses, and so they will take out loans to cover transportation and other personal items, she said.

For other in-state recipients, debt is unavoidable even with a Pell Grant and the addition of scholarships and other financial aid.

UA junior and Pell Grant recipient Billy Cook expects to accumulate about $15,000 in debt for his undergraduate degree in history and political science.

Cook, 21, from Gravette, said he received other financial aid along with the Pell Grant, including the scholarship lottery, Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant and other smaller scholarships.

“I think the one that made the most impact was of course the Pell Grant, because it’s a fairly large sum of money in terms of a scholarship or a grant. It’s made a good difference compared to the other ones,” Cook said.

Nearly 55 percent of all undergraduate UA students are receiving grants or scholarships, according to 2017-18 College Navigator data. For the upcoming academic year, $5 million is being added to the scholarship budget for freshman and other students, Blevins said.

The UofA chancellor’s decision to put $5 million into the scholarship budget shows there is a focus on financial need of students, McCray said.

Arkansas ranks 5th in nationwide poverty, with approximately 17.2% of residents living below the poverty line in 2018, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“We’re shooting for 85% of our budget going to in-state students. It’s normally a little more than that,” Blevins said. “The motivation was to make college more accessible for Arkansas students.”

In order to receive a Pell Grant, students must fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA. The application opens Oct. 1 for the upcoming academic year, and students should complete the FAFSA by Dec. 1, McCray said.